Reckoning with Modernism

Ribak/Mandelman House, Taos, New Mexico

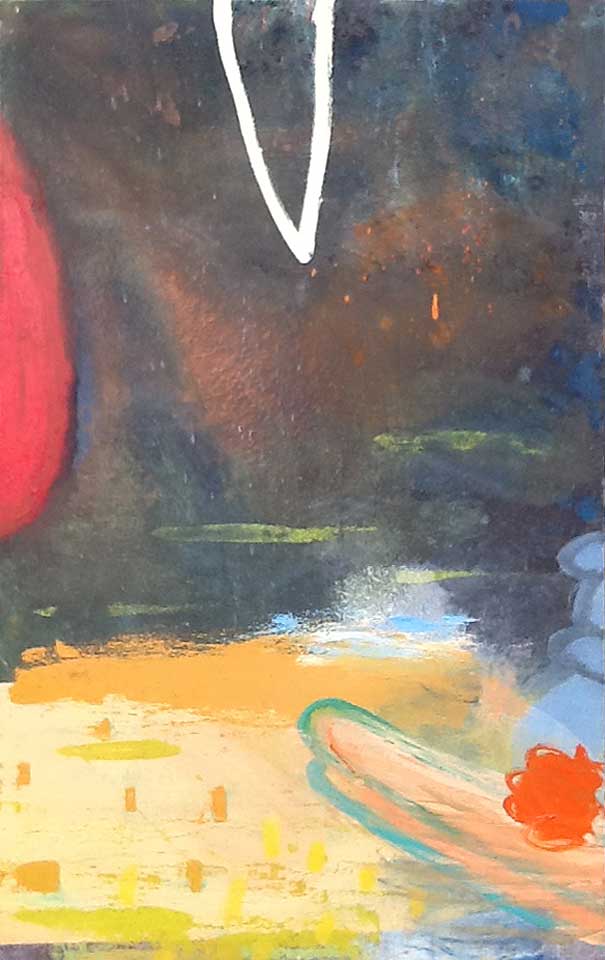

If we begin with Baudelaire, we are directed to be modern at all costs. I remember as a child delighting in anything French. The expression ‘a la mode’ brought to mind big hair and crinoline underskirts as well as heaps of ice cream on top of anything. Being modern was living in glass houses and wearing pointy shoes. To be modern at all costs is a tall order for a land of consumer sheep following tail to tail through the drive up lane. But this is not what Baudelaire means in my mind. Philip Guston says that Baudelaire wanted to put the smell of armpits in his poems. He saw modern as a way of being, the way he felt life. This is a good place to begin.

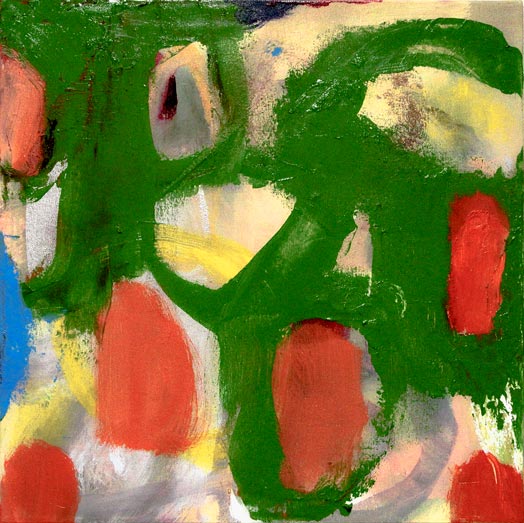

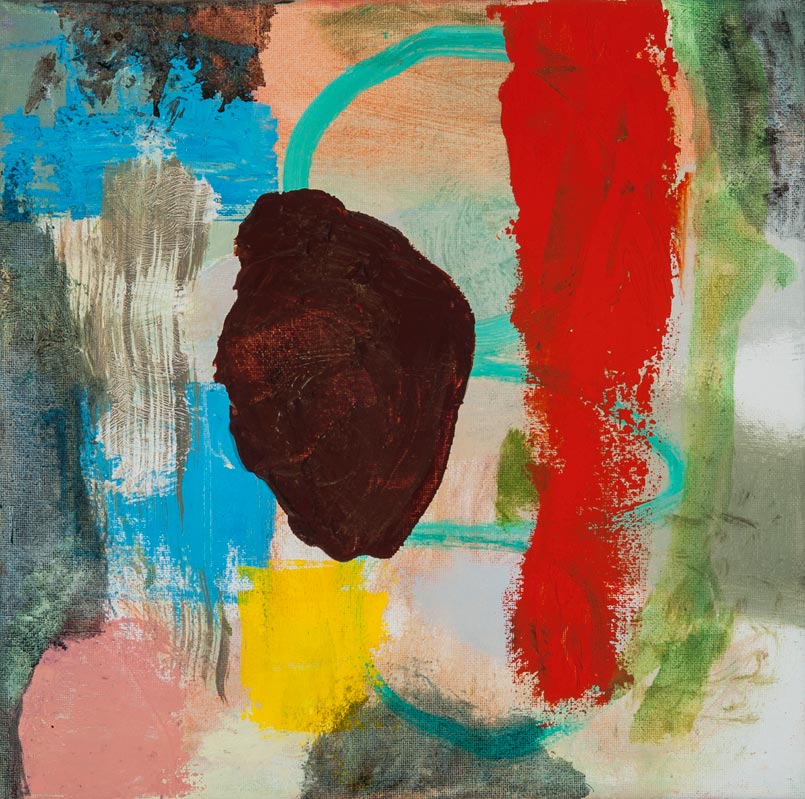

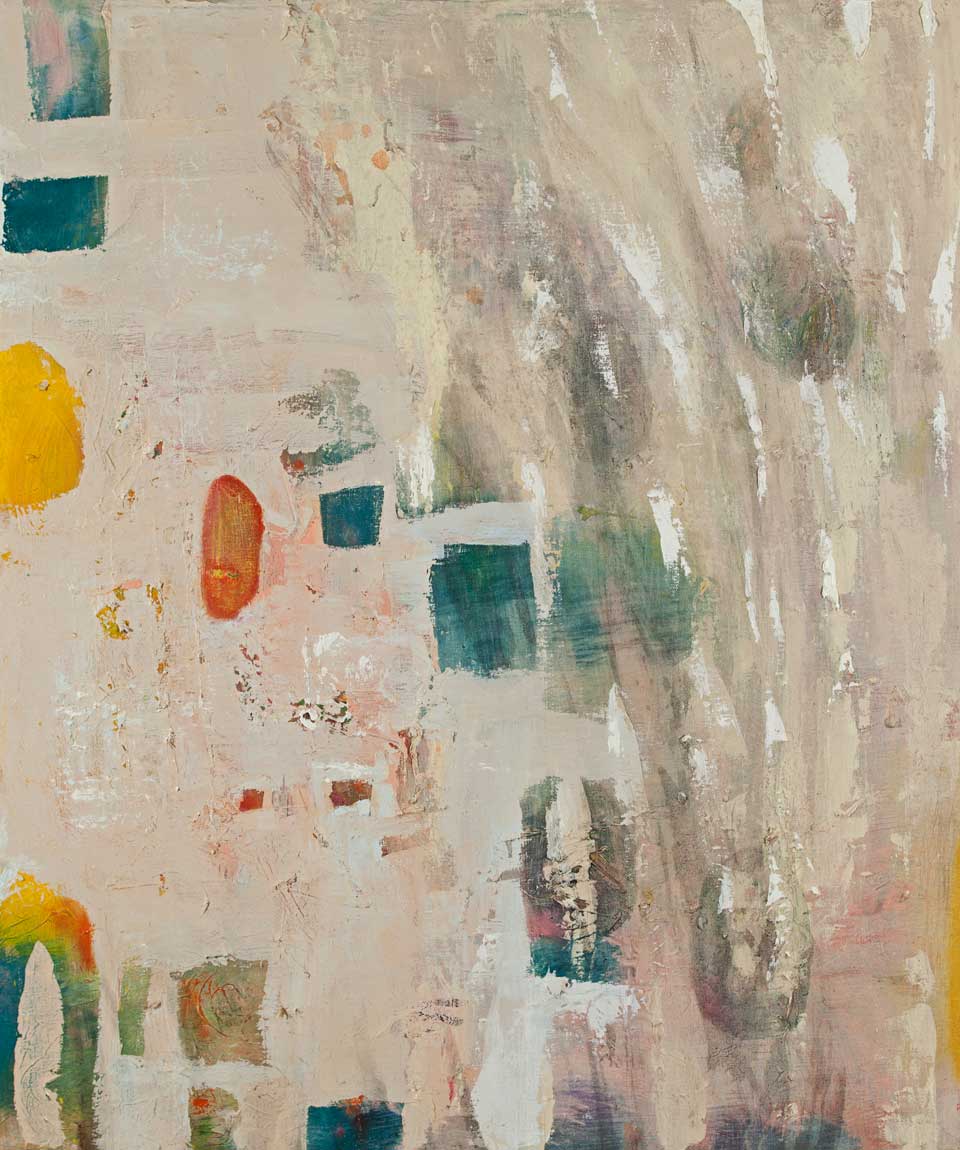

I begin a painting in one of two directions. Either I reach a place devoid of reference relying on the paint to direct me. This is as difficult as beginning a meditation and clearing out the mind of all the debris of the day. But when it is good, it is as if the painting reveals itself in some mysterious way, allowing me to see what it wants, not what I demand of it. I have a big old clock on the wall of my studio my brother rescued from a bate shop. On the clock hangs a sign THE TIME IS NOW. And by bringing the paint and myself back to the “now” I sometimes find that that great philosophical problem I want to solve in my painting has just been accomplished by following the paint. This is what my teacher Jorge Fick tried to knock into me-the medium is the metaphor. By feeling the lushness of the paint, of the drag of the brush against the dry surface of linen says something about that very moment. And by saying something about that very moment, one is talking about the history of the world or quantum physics or convenience stores.

Or I begin the work by continuing an experiment in synsethesia with my friend and poetry translator, Sonja Kravanja. We began the Poem Paintings 20 years ago and started up this process again in January 2013. Sonja sits in a big chair in my studio and reads from her translations, sometimes in Slovene, sometimes in English. Something happens. I may not know cognitively what she is reading, but emotively I am swept away and it becomes like a dance hearing the words that become color or stroke. Of course, there is the touch of reference. But when it is really humming, I am trance-like; I become the conduit for the sound of the poem to meet the canvas.

Delacroix really gets there with modernism. In his diaries, he writes “Modern is the man. Not style.” I think what he is getting to here is that one comes from an authentic, gut place where one is moved by the emotion of the moment. By holding witness to the now we discover the universal.