High Brow Low Ride

PHILSPACE, Santa Fe New Mexico

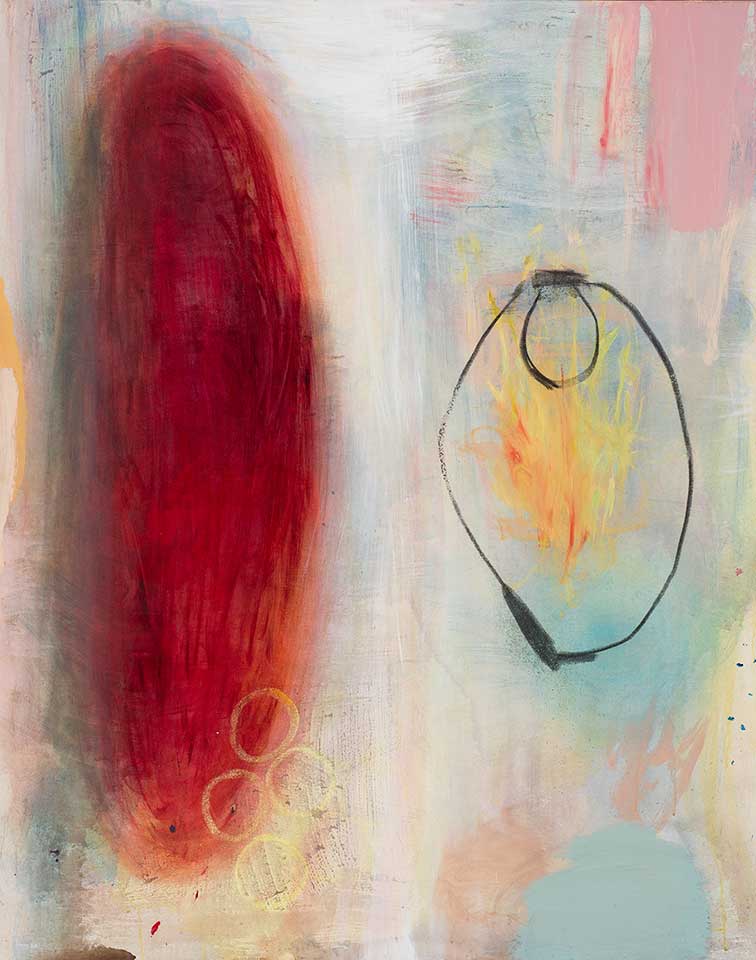

The summer after Trump’s election, Horton-Trippe visited the non-profit Santa Fe YouthWorks and met a confident, elegant woman leaning against her low-rider in the parking lot. She was the President of the Española Low Rider Club, “a young woman with foot high hair and eyeliner winged to the moon” who, with a pocketful of wrenches, was dismantling the patriarchy bolt by bolt. This woman became the impetus for a body of new work — an exploration of command in the feminine — and provided a colorful palette for Horton-Trippe’s own celebratory cry of NO MORE to the suppression of women in our culture. On huge canvasses, in colors and gestures that celebrate the reunification of nature and power, Horton-Trippe creates fertile territory in which big hair, hot pink, and shiny surfaces are elevated to an aesthetic of honor.

A portion of the sale of these works will be donated to Santa Fe Youthworks.

The Magazine Review, April 6, 2018: Shelley Horton-Trippe: High Brow Low Ride

Raising Fierce Beauty

How do we answer the question of finding art, beauty, love, hope in our current moment. As much as these might seem to be superficial, placating tropes, overly romantic or ineffective, there remains a deep desire to find solace through the visual world. In fact, in the face of the ceaseless onslaught of daily events, the drive to seek power and strength through creation has only grown stronger.

To me, art has always been synonymous with mothering. Again, the concept of mother, mothering, motherhood might seem to be soft and overtly feminine, much like beauty and art. But in my life, as the daughter of a bold artist, woman, mother, the potential of art to support life, growth, and change has been a daily lived experience. I have had the privilege of experiencing the process of this nurturing first-hand. The profound link between the fostering of an artwork and the fostering of a child is often neglected in art criticism and theory. So many of our most successful artists, particularly women artists, have been celebrated for their childlessness, as if art and children are mutually exclusive and art emerges as the higher calling. The fallacy in this determination is clear and yet the bias remains strong.

I explain this all in order to situate my emotional response to Shelley Horton-Trippe’s new body of work. I come to this work as daughter first, art historian second, which I firmly believe is the most honest path to this work that I can take. I have seen these paintings take shape over the last year as we stare down the horror of what our world has become. And I have seen these paintings grow from color sketches between my mother and my daughter, the seeds of splotches and patterns and lines and houses and flowers and pet dogs. I have seen the secret language between these two anchors of my life as they make together; a language that I witness but do not speak with them. But this is what I see, the private experience of these works. The brilliance here is how this private essence edges out to the viewer beyond our private realm of mother, daughter, granddaughter.

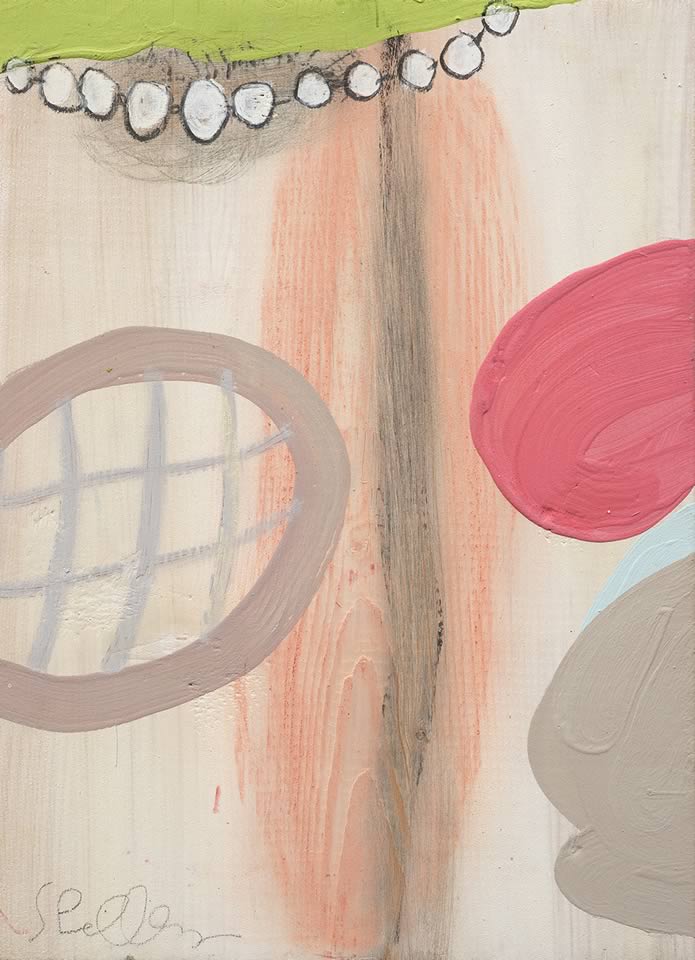

But then there is the work. The end result of the private process of making reaches beyond the internal and personal to the larger world of art history, politics, identity, philosophy, and popular culture. In High Brow Low Ride Shelley recalls the power of the Finish Fetish painters of 1960s Los Angeles (and Taos, of course). The high-gloss and bold colors of car culture, the sheen of Judy Chicago’s very early work, Ken Price’s vibrant, amorphous blobs. But she also, in the same moment, on the same surface, harkens back to the Romantics and the power of landscape as if she zooms in on those zones of abstracted washes and waves of color that are so utterly contemporary. Shelley’s paintings find a place for the past to merge with the present and for landscape to bump up against the hard sheen of a lowrider. This is where the hard and the soft can meet and it is a space that we are all seeking build and reside within.

Ultimately, in these paintings Shelley is willing into being a space for joy – as all mothers do. The architecture of her colors reveals a capacity for not only seeing alternatives to the mundane and the painful, but building them for all of us to escape into. The private gift comes to be the public revealing as it is nurtured and mothered from conception. The paint is applied in practiced layers. A balanced structure emerges from the possible chaos of sketched lines, rough brushstrokes, fading washes. The result is not just mother-comfort but a fierceness that we have all seen building to crescendo in recent months. These works are that beauty, love, hope that we need; the palliative and the propellant.

Bess Murphy, PhD

February 2018